Composting

If you want to become a great food gardener, you’ve got to get rotten. Soft, dark, spongy rotted down organic matter is the secret of healthy soil. It is the gardener’s black gold, so make like a pirate and say “Aaaaaaagh!” for this is the ultimate buried treasure.

The healthier your soil, the healthier – and more nutritious – are your plants; and ultimately, the healthier are you! Ms Nature, well she likes nothing more than an organic-matter-rich chocolate coloured soil. But try as she might to make this everywhere she possibly can, a lot of organic matter is lost to the atmosphere before it ever makes it into the soil, as it dries out and is exposed to UV rays, especially here in on this hot dry continent of Australia.

So can we help Nature do what she yearns to do? Yes indeed! We can set up the most ideal conditions for nutrient cycling in our own backyards, and in a word, the way we do it is composting. Composting — the art and science of using billions of tiny microbes to transform your food scraps and other organic waste into rich spongey organic matter — is the secret behind the sweetest tomatoes, the greenest silver beet, and the healthiest cabbage the world has ever seen.

Now you might already be squirming about the smell of compost, so let’s get one fact straight: a well-managed compost smells good. It doesn’t attract rats and cockroaches, it doesn’t turn your neighbours against you, and it will be finished and ready to use within six or eight weeks. In fact, when your neighbours see what the compost does to your garden they’ll be over to ask how you did it! For composting is the cornerstone of any sustainable vegetable garden.

A little secret: your compost is alive. Alive with billions of tiny friends. And the trick to a healthy compost pile is giving these microbial comrades just what they need. You’ll be relating to these teeny critters in no time, as what they need is the right amount of three things that we need too: food, air and water.

Food

This right here is where beginners can get it wrong. Because it’s not just any organic matter than feeds a healthy compost pile, but the right combination of organic matter. A compost pile needs the right combination of foods high in nitrogen, which are often green and wet, and foods high in carbon, which are usually brown and dry.

| Foods high in nitrogen | Foods high in carbon |

| food scraps cow manure horse manure grass clippings feathers hair Foods very high in nitrogen (activators) chicken manure blood & bone | straw dry leaves newspaper sawdust woodchips cardboard |

As a rule of thumb, for every one part of food high in nitrogen, you need one to two parts food high in carbon. Too much nitrogen and your compost will stop being a compost and start being a smelly putrid mess (you’ll find out why below). Too little nitrogen and it will take forever to be ready. Small amounts of activators like chicken manure or blood and bone can help fast track your compost.

When you build your pile, you should layer your food materials, alternating between your carbon-rich materials (e.g., 10cm thick layers of straw) and your nitrogen-rich materials (e.g., 5cm thick layers of food scraps or cow manure).

We recommend excluding dog and cat manures (although see our page on worm-composting dog poo). Apart from that, follow the composter’s adage: ‘if it has lived, it can live again’. Hair, coffee grounds, old woollen socks; get them all in there!

Air

Inside a healthy compost pile billions of tiny bugs are breathing. These bugs, or bacteria, breathe in oxygen, just like us. If the oxygen runs down, the bugs change into bugs that can handle lower oxygen levels, called anaerobic conditions. These bugs are the bad guys and they do little farts and make bad smells. This is why a compost pile with too much nitrogen smells bad.

The nitrogen makes the bacteria party hard, and their combined respiration uses up all the oxygen inside the pile, which sets the conditions for the gatecrashing anaerobic bad guys of the microbial underworld. The result is also extra greenhouse gases like methane, which is what we don’t want. If your compost smells bad, you are losing precious nutrients to the atmosphere. Luckily we don’t need sophisticated equipment to know when a compost pile is going anaerobic, your nose knows a good compost pile from a bad one.

To maintain enough air in your pile, you need to employ strategies like:

- poking holes in your pile

- resting your pile on a layer of coarse branches and twigs

- turning your pile every once in a while with a compost fork, rotating compost bin, or compost screw

- including about 5% course wood chips, small twigs or bark in your pile to make space for little air pockets (especially if it is all finely chopped material like grass clippings)

Water

Like us, the compost microbes need to drink. What they need, in fact, is a continuously moist medium in which to make their living. Not soaking wet, or tinder dry, but moist, like a freshly squeezed sponge. If your compost is too dry, add water, turning it to get the water in if necessary. If your compost pile is too wet, spread it out and and let it dry a bit before reforming, or mix in some dry stuff like shredded newspaper or dry pea straw.

Specific Ways of Composting

There are various ways you can meet the above aims to do with food, air and water. The most common are:

Hot compost. If you make a big enough pile the combined body heat of all those little bugs cooks and speeds up the process (killing some plant diseases and weed seeds in the process). To make a hot compost, stockpile organic matter, or source it in bulk, then build a pile of at least one cubic metre in size. Any smaller won’t work as the bugs need a minimum volume to create a critical amount of heat.

Our cypress compost bays look good, smell good and have removable sleepers to make turning your compost easy. They aren’t exclusively for hot compost but they are big enough if you want to use them for it.

Check out our cypress compost bays!

Cold compost: The most common form of composting is to put your left-overs and kitchen scraps into a black plastic compost bin. If your bin has no or few air holes, it is best to drill a few more into the sides. Layering your scraps with straw, autumn leaves or shredded paper or wet cardboard for that ideal carbon:nitrogen ratio, and fresh smells. A compost screw is a must for rapid breakdown.

Worm farms: Worms make a fantastic compost. You can only feed them soft stuff, but they are more forgiving with getting carbon:nitrogen right, they aerate the compost for you, and produce a wonderful product. See our page on worms…

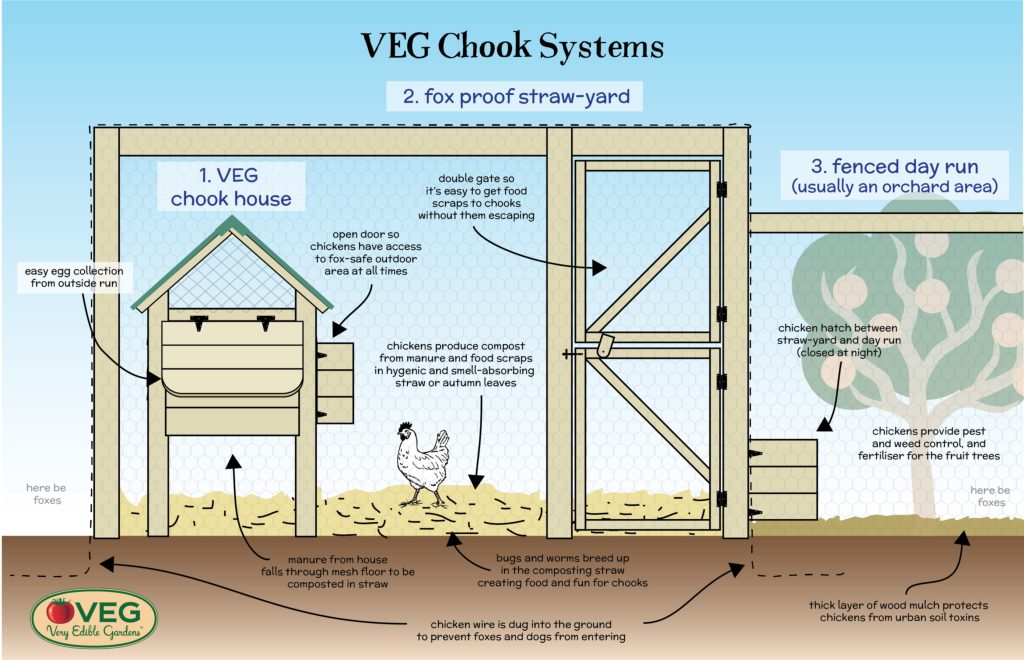

Chickens: The power of chook can be harnessed for your compost-making, and what’s more they’ll thank you for the opportunity. There’s nothing chickens like more than scratching through straw and food scraps for seeds and bugs and in the process they can create a great compost mix. Make a thick bed of high-carbon material like autumn leaves, straw or sawdust and throw your scraps on top. We build systems that put chickens to work making compost while they have a fantastic time!

Check out VEG’s marvellous chook-powered straw-yard composting systems!

Just Have a Go

Go on – get out there, give it a go! Don’t worry too much if things are going a bit slimey and stinky, just add some high carbon material and mix it in. If things are taking too long to break down add some high nitrogen and moisture. You really can’t go too far wrong, and you’ll soon be getting your garden growing gang busters, and you’ll be hooked for life!